Keeping to the main road is easy, but people love to be sidetracked.

Lao Tzu

I’ll labour night and day to be a pilgrim. Hymn 564

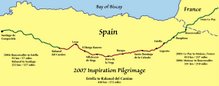

As you may know, we did not walk the entire 1521 kms/960 miles in one trip; we broke it up into four segments. Hence, for the next three springs, we researched where we were going, I would phone across the ocean to make reservations for the first two weeks, we’d pick up the packs, and hit the road. Only that first spring did we have the sense of total confusion and feeling lost; on subsequent trips we better understood how the system worked and could re-enter with minimal difficulty.

After the first spring, we knew what the daily routine would be and I would find myself looking forward to its simplicity. Just as a monastic community has its rhythm, so does the pilgrim community. Depending on where you stayed determined reveille. If we stayed in one of the dorm-like refugios, the rustling of plastic bags (always!), thundering footsteps, no matter how quiet people tried to be, and whispers would wake us up. If we stayed in a more civilized place like a small hotel or B&B, we’d get ourselves going. No matter how many times we did it, it still would take us an hour to pack up (because the night before we had totally unpacked, especially if we had to use our sleeping bag because it resides in the bottom of the pack), get our water set and boot up. If it was raining, putting on the rain gear added time. Before leaving, I would pull out the little slips of paper on which people had written their prayers, and I would go through them so I could carry them with me in the course of the day. I had a rota going so I would say: OK, you need to remember to pray today for so-and-so.

Sometimes we would set off having had breakfast, other times we would have to walk a while before getting that first cup of coffee, orange juice and croissant. The first half hour was getting the kinks out of one’s system, adjusting boot laces, wondering if that tendonitis in the knee was going to kick in, or if that deep blister was going to hurt more than it did the day before. At the beginning of the day, there sometimes would be short stops to get organized. Then we would walk for another three hours or so before stopping for a break. On long days, we’d try to knock off 20kms in the morning before lunch because after lunch, the walking was always harder. On super long days (35kms) we would crank out as much as we could and take as few and as short breaks as possible. Afternoons and early evening, we’d begin to wind down — not intentionally but simply because we’d been walking all day and it was one day piled up on top of another. The last hour, no matter how far or short a distance remained, could be the worst and there were days I felt like a moribund tortoise.

When we’d get to where we were to spend the night, we’d change into our one other set of clothes (our ‘evening clothes’) and do laundry of what we’d had on. Everything we wore is synthetic meant to dry quickly. I would try to journal where we’d been or anything of interest. Sometimes sleep would get the better of me. Then it was off to dinner, meeting up with other walkers, and then back for an early bedtime because we’d be doing the same thing the next day.

Anyone who has walked either the Long Trail or the Appalachian Trail knows that there is a whole trail mentality and community. On the LT and AT people give themselves trail names, leave messages in notebooks at the shelters, help one another out and sometimes even share food (we do because we are always short haul walkers).

So it is on the Camino. We rarely knew other people’s names (I sometimes felt it was like being in a huge twelve-step meeting) so sometimes would end up giving them nicknames like Dog Man (because he walked with his dog) or the Swiss woman, the horse people (self-evident), the photographer, or the nice Danes who shared their lunch with us. (I suspect some called me gimpy the third year of walking.) Still, we tended to walk with a pack of people insofar as most people started from and ended up at the same places. You’d recognise faces, wave to one another, ask the essential: how their feet, knees, shoulders and back were holding up. We’d share chocolate, bread and cheese. If someone looked lost, we’d whistle and wildly gesticulate to get them back on the path. The Camino community watches out for itself.

Most walkers were what I would call ‘seekers,’ the folks who would say they were spiritual but not religious, in other words, plugged into the institutional church. It being France and Spain, we ran into a lot of lapsed Catholics. Despite their lack of church affiliation, they would pick up on the inherent spirituality found in walking a pilgrimage route that dates back to the 9th century and on which thousands and thousands of feet have trod.

Claiming the title, ‘pilgrim,’ took some time, however. Initially, I was someone from the Untied States, a French medievalist, an Episcopal priest. But pilgrim? Gradually, the name took. Perhaps it was being wished every day buen camino, have a good trip, by so many people along the way. Or it was people calling us pilgrims. Well, we were. That’s what it said on our credencial: we were walking this pilgrimage route on foot for spiritual reasons. We would stop in any open church we could find (in the Alteplano of Spain, our success rate was dismal); I would light any candles I could find (lots of real ones in France, lots of electric ones, which I just can’t bring myself to ‘light’ in Spain) and we would sign the book that countless pilgrims before us had signed. These books both in Spain and France contain the prayers and thoughts of pilgrims and I would always read the page on which I signed. If I had time (i.e., if we were taking a break in a cool church on a hot day), I would go back several pages. We were walking for the MDGs in 2007; in previous years, I had other intentions for which I was walking. Eventually, I claimed being a pilgrim in my heart as well as in my mind and on subsequent trips, I refound the pilgrim spirit within hours.

Oftentimes people set off on a pilgrimage with a set idea of what they are going to discover. I tended to go with an open heart and mind, trusting that over the course of two plus weeks of quiet time, God would reveal Godself in some way to me. My first year I think the message was a continuation of sabbatical: what does it mean to live simply in a pared-down life? The second year, I was discerning whether or not to go forward in a conversation with a congregation and on the second-to-last day, the message was quite clear that I should. The third year I learned what it meant to live with daily pain and to have more compassion for others who suffer with it, and to have patience with myself. And the last year, I lived in one of life’s hard lessons, letting go. I found that the patterning rhythm of walking, the quiet (we would talk sometimes but other times walk for an hour or two in silence) would allow for God to come close.

We experienced four departures and four arrivals. Each arrival had a different impact on me. Obviously the most significant arrival was that of Santiago. After all, those who walk the last 60 miles (100 kms) receive the coveted Compostela (mine hangs in the office here) which I received on 6 May 2004 in a jubilee year. The closer we got to Santiago the more crowded the Camino got and the harder it was to find lodging. That was when I was set to make phone calls to hotels to book us rooms ahead of time so we could walk in peace. We decided not to stay at the massive pilgrim center, a former army base, five kms out of Santiago but instead walked in our last day on a 18 km walk. As we got close to Santiago the heavens dumped on us for good measure. We got to the outer road of the city and realised this was it; we were about to arrive. We came in through the side street, walked through a passageway and found ourselves at the cathedral, this huge gaudy Baroque building (the façade covers a Romanesque tympanum). My first unvarnished thought when I saw it was: So this is the object of my desire? This is what I have been walking two weeks for? My next thought was: And we have to climb up all those stairs to get inside?

When we arrived two years later in Saint Jean Pied de Port, the end of the 450-mile French Way of Saint James, I started to weep. It wasn’t just because I had just walked two weeks with two broken toes, it was because I realised I was finishing this part of the pilgrimage. Even though I knew the next day that we would be walking over the Pyrenees to Roncesvalles, Spain, I still had this deep ache that we were leaving the pilgrimage route.

In 2007, when we walked the last 20 kms of this 1520km trek, it seemed unreal. For four springs we had packed up our lives, entered into this flowing stream of humanity headed westwards and now we were truly ending the quest. We walked into a very small hamlet in the mountains and it was at a little chapel run by a monastic order that I lit my last candles, said my last prayers and left the Camino. The next day we watched the pilgrims begin their day but we had already stepped off that treadmill. It was very hard to see. Each spring, I get intense longings to rejoin that stream of humanity.

We learned as so many other pilgrims do in those moments is that the ending is not an ending and it is not what matters. What one finds out is that the journey is what matters. A mural on a wall outside of Nájera contains a poem painted over several panels. It asks: ‘Pilgrim, what attracts you to the road?’ It then gives possible reasons why and on the last panel the answer appears: ‘Only the One above knows.’ Elsewhere in a refugio, pilgrims will read: Peregrina, you do not walk the path, the path is YOU, your footsteps, these are the Camino.

What one realises is that throughout one’s entire life, one is a pilgrim. One may never set foot on a pilgrimage route, but one is a pilgrim as one tries to hear what God might be saying, as one prays, as one participates in the community’s life of prayer.

T. S. Eliot wrote:

We shall not cease from exploration

And at the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

Arthur Paul Boers reflects on this stanza: ‘We shall not cease exploration’; we are always sojourners moving along the way, not just when we are official pilgrims. That ongoing restless wandering perpetually brings us back home to ourselves. Just as the Camino showed me more deeply things I already knew about myself, so it invited me to be acquainted with my home and life in new ways, ‘for the first time.’ And, as Scott Russell Sanders notes: ‘Pilgrims often journey to the ends of the earth in search of holy ground, only to find that they have never walked on anything else.’ (1)

+

We are about to start our Lenten pilgrimage. We will find that the path is us. We may not know where the road will lead; we follow day by day…. Come Easter, we will arrive at a point and place in time but we know that next year the pilgrimage route will call to us once again. There is some consolation in that knowledge; whatever we don’t get to this Lent, we have all year to walk with it. When we arrive at Easter, remember to let your soul catch up with where you have been. Be in the present moment.

As we walk into Lent, may we pray: Lord, take me where you want me to go; let me meet who you want me to meet; tell me what you want me to say, and keep me out of your way. (Mychal F. Judge)

END NOTE

(1) Arthur Paul Boers, The Way is Made by Walking: A Pilgrimage Along the Camino de Santiago (Downers Grove, IL: Intervarsity Press, 2007), 178.

PHOTO

Saint Jean Pied-de-Port, 28 May 2006.